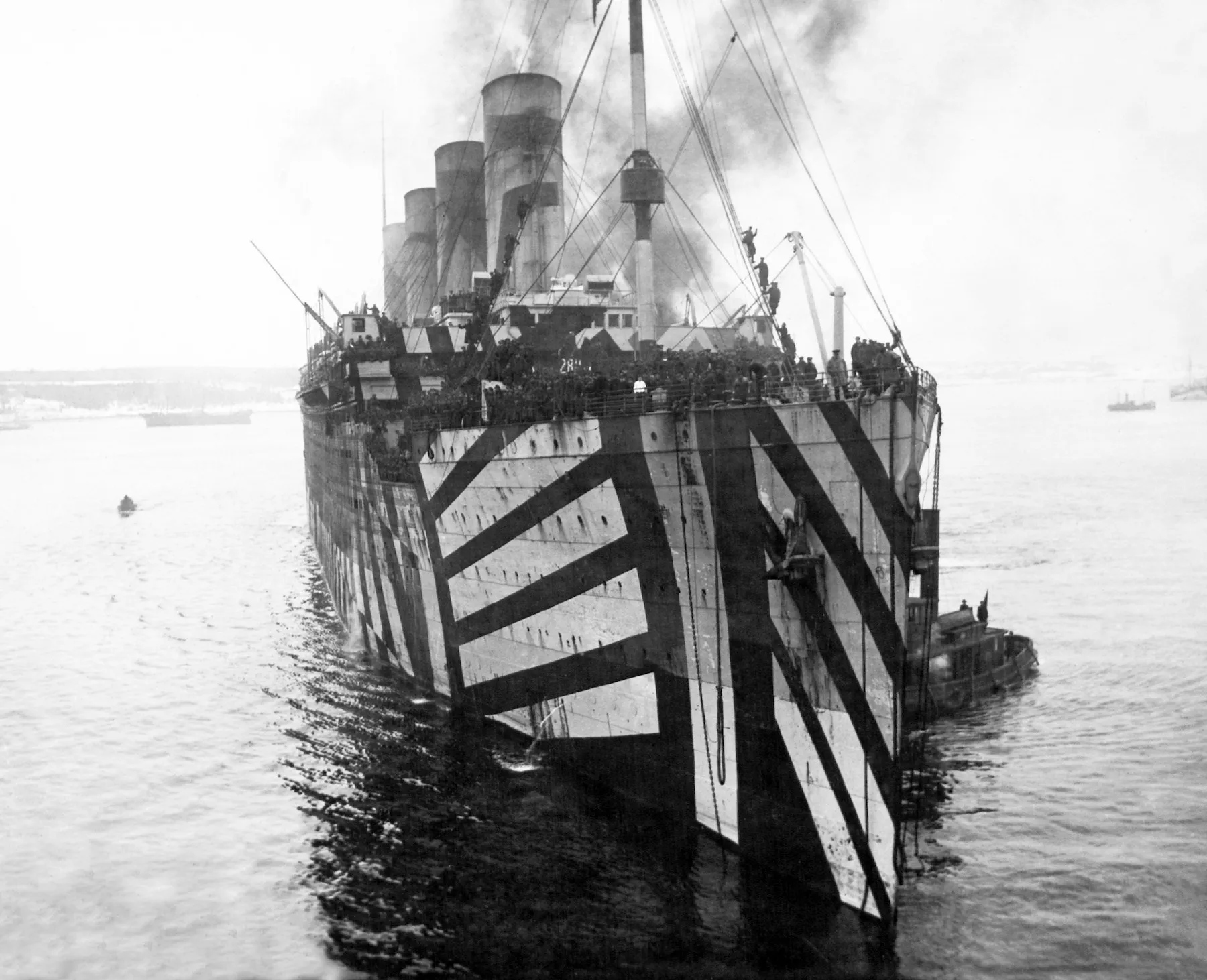

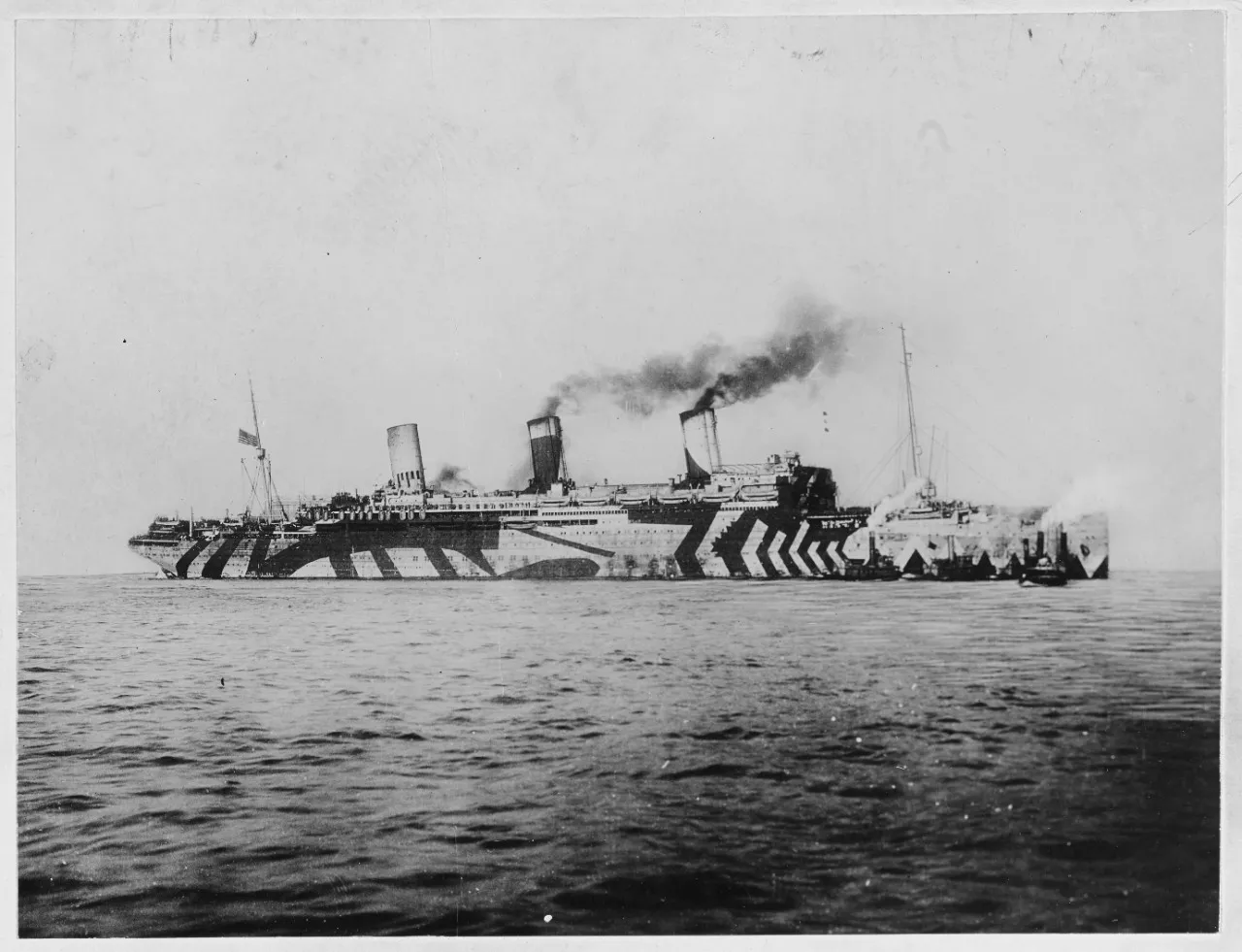

During World War I, Allied navies started implementing shocking, cubist-inspired “dazzle” paint jobs on ships. The now-iconic geometric designs were intended to throw off the visual perception of German U-boats crews and prevent them from accurately targeting ships with torpedoes. Conventional wisdom claims the bizarre camouflage pattern worked and helped turn the tide of Great War naval battles. But new research reevaluating one of the only rigorous studies testing that hypothesis suggests those conclusions were probably overblown. Researchers now claim another phenomena known as the “horizon effect” may have actually done more to throw off submarine gunners than the wacky aesthetic.

The study, published last week by Aston University researchers in the journal i-Perception, recreated one of the few solid quantitative studies on dazzle ship effectiveness, updating the methods to meet modern scientific standards. The revised findings claim the original study “substantially overestimated the effectiveness of dazzle camouflage.” While the modernist designs may have played some role in distorting perceptions of a ship’s movement and direction, the new study found similar effects also occurred with ships painted in standard, single-color palettes. According to the researchers, U-boat gunners viewing ships from a distance likely fell for an optical illusion that made the vessels appear as if they were traveling along the horizon. That illusion likely occurred whether the ships were “dazzled” or not.

“These reappraised findings resolve an apparent conflict with the second quantitative experiment on dazzle ships conducted over a century later using computer displays online” researchers write.

Dazzle: A different kind of ‘camouflage’

The dazzle paint scheme originated around 1917 as a direct response to unyielding German U-boat attacks. German ships famously adopted an “unrestricted submarine war” policy at the start of the year which reportedly resulted in hundreds of sunken ships, both military and merchant, in less than one year. One of those downed boats, a British hospital vessel called the HMHS Lanfranc reportedly resulted in 40 deaths. Looking for a solution, English artist Norman Wilkinson approached Britain’s King George V with models of ships adorned in zig-zag and checkered patterns in shades of gray, black, white, green, orange, and blue. Wilkinson claimed these odd shapes, when viewed from a distance through a U-boat periscope, would distort the ship’s appearance just enough to make it difficult for submarine operators to accurately track and target them with torpedoes. Convinced by the demonstration, King George approved the implementation of dazzle designs across the British fleet.

Wilkinson’s dazzle approach followed on the heels of other, less practical proposals. Shipmakers had reportedly tried at various times to cloak vessels in mirrors and paint them to resemble giant clouds and whales. American inventor Thomas Edison even reportedly pushed forward an idea to reconfigure ships to look like floating islands lush with foliage. All of these ideas ultimately failed because they couldn’t account for the constantly changing environments and weather conditions at sea. It simply wasn’t possible to fully camouflage a ship in a way that consistently blended it into its surroundings. Dazzle took an entirely different approach. Rather than trying to disappear, the unorthodox geometric shapes aimed to confuse an observer’s perception of a ship’s movement and orientation from a distance.

Did Dazzle actually work? New research casts doubt.

Though widely adopted by both British and American vessels during the war, dazzle camouflage was mostly implemented based on assumption rather than solid evidence. Limited, high quality empirical research from the time actually measured whether or not the dazzle worked as advertised. One of the only remaining quantitative studies on its effectiveness was conducted in 1919 by an MIT naval architecture and marine engineering student named Leo Blodgett as part of his thesis.

In the study, Blodgett painted model ships with dazzle patterns and placed them in a mock battle theater. He then observed them at a distance through a periscope and claimed the dazzle effect confused the observer’s perception of the ships’ movement. But when the Aston University researchers looked back over the findings they found several holes in the study, notably in Blodgett’s control group, that didn’t measure up to modern standards. Those shortfalls in the control experiment, according to researcher and co-author Samantha Strong, made Blodgett’s experiment “too vague to be useful.” The Aston researchers went back in and created a new control experiment based on edited images of the original results. The newly improved methods showed the optical illusions occurring in cases where the ships did and did not have the dazzle paint.

“We ran our own version of the experiment using photographs from his thesis and compared the results across the original dazzle camouflage versions and versions with the camouflage edited out,” Strong said. “Our experiment worked well. Both types of ships produced the horizon effect, but the dazzle imposed an additional twist.”

If Blodgett’s initial findings held true, the researchers noted, the front (or bow) of the ship would have consistently appeared to twist away from the direction it was actually traveling. In reality, the researchers found several instances where the observer perceived the ship’s bow twisting back around, even as it moved away. This illusion, they argue, likely had more to do with the “horizon effect”—a phenomenon where a ship appears to travel along the horizon regardless of its actual direction—than with the dazzle camouflage itself. The researchers went on to note that ships traveling up to 25 degrees relative to a horizon will still look like they are traveling alongside it from the observer’s point of view.

“The remarkable finding here is that these same two effects, in similar proportions, are clearly evident in participants familiar with the art of camouflage deception, including a lieutenant in a European navy” Aston University Professor and paper co-author Tim Meese said in a statement.

Revealing as the findings are, they don’t necessarily mean dazzle was completely ineffective. As noted in a 2016 Smithsonian report, merchant ships clad with the dazzle pattern during the war were reportedly granted lower insurance premiums. Some ship captains at the time also claimed crew morale appeared higher on ships with the dazzle pattern than those without. Even if the actual illusory effect of the dazzle was minimal, people bought into the hype and believed it was effective.

In other words, never count out the placebo effect, even during times of war.