Solar flares are a great reminder of our sun’s truly immense power. Despite our solar system’s central star being roughly 93.955 million miles away from Earth, its flares have enough energy to cause blackouts and mess with radio communications. Studying the intricacies of solar flares and other space weather could help us Earthlings improve disaster plans when the sun’s excess energy is headed our way.

Now, the National Science Foundation’s Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST) has captured some incredibly detailed images of a solar flare. These new images may help us better understand the sun’s magnetic field and improve space weather forecasting in the future. The findings are detailed in a study published August 25 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

On August 8, 2024, the sun emitted a highly-energetic X1.3-class solar flare. X-class flares like this one are incredibly powerful and can even interfere with technology here on Earth. At about 4:12 p.m. ET, the study’s team used the DKIST to observe and image the solar flare during its decay phase towards the end of the event.

“This is the first time the Inouye Solar Telescope has ever observed an X-class flare,” Cole Tamburri, a study co-author and an astrophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in a statement. “These flares are among the most energetic events our star produces, and we were fortunate to catch this one under perfect observing conditions.”

The astronomers using this sophisticated telescope observed these special solar features at a very small wavelength called H-alpha wavelength (about 656.28 nanometers). Observing the sun’s activity in such detail can show aspects of our star’s behavior that other solar telescopes can’t pick up.

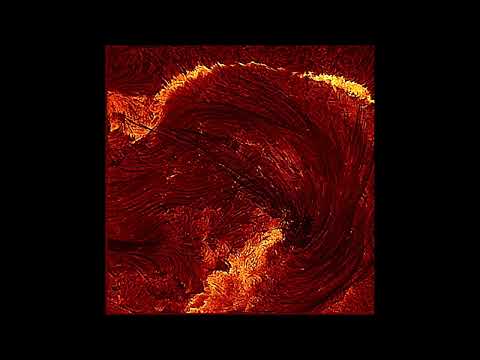

They captured solar features called coronal loops—wispy, arches of plasma that follow the sun’s magnetic field. Coronal loops often occur just before a solar flare begins and persist throughout. The coronal loops themselves may trigger the bursts of energy often seen spewing from the sun’s magnetic fields. They are also very hot—with some coronal loops topping one million degrees Fahrenheit.

The team focused on hundreds of these razor-thin magnetic field coronal loops above the solar flare ribbons. On average, the loops were roughly 30 miles across, but some were right at the telescope’s resolution limit of 15 miles.

“Knowing a telescope can theoretically do something is one thing,” added study co-author and solar astrophysicist Maria Kazachenko. “Actually watching it perform at that limit is exhilarating.”

Astronomical theories have suggested that coronal loops may range from six- to 62-miles-wide and the DISKT makes confirming this range possible.

“This opens the door to studying not just their size, but their shapes, their evolution, and even the scales where magnetic reconnection—the engine behind [solar] flares—occurs,” said Tamburri.

One of the most tantalizing theories is the idea that the coronal loops may be the foundational building blocks of how solar flares form.

“If that’s the case, we’re not just resolving bundles of [coronal] loops; we’re resolving individual loops for the first time,” Tamburri adds. “It’s like going from seeing a forest to suddenly seeing every single tree.”