If the engine and/or manual transmission is coming out of your car or truck for whatever reason, you’ve probably considered giving the flywheel some attention at the same time. Similar to installing a fresh clutch, it’s one of those tasks that gets done when access is available, even if slightly ahead of schedule. The lowly flywheel — a nondescript flat metal disc — doesn’t get as much attention as other more glamorous modifications like air intakes or adding boost, but it actually serves several important purposes.

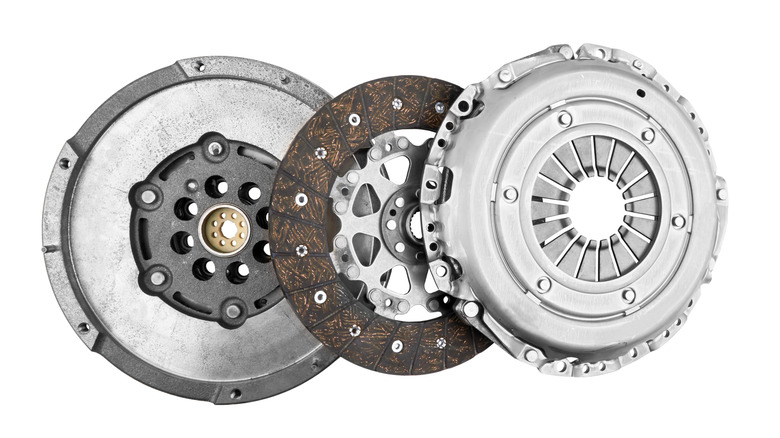

To start (pun intended), a flywheel has teeth around its perimeter that mesh with a gear on the electric starter motor to get your engine cranked over and running. Next, the flywheel serves as a large, smooth surface for the clutch to grab with friction when the clutch pedal is released. Typically, a flywheel is attached directly to the crankshaft at the back of the engine block, so it rotates at the same rpm as the crank. Besides providing mating surfaces for the clutch and starter motor, a flywheel also stores rotating energy and acts as a vibration dampener of sorts.

During a clutch swap, it may be possible to resurface and reuse your existing flywheel. But you might also opt to replace it with a brand-new unit, especially if you’re eying up a lightweight flywheel to increase effective horsepower. While increasing horsepower is almost always a good idea, lightweight flywheels definitely aren’t appropriate for every situation.

It’s not ideal for drag racing

There’s a sort of general consensus among gearheads that a lightweight flywheel increases horsepower but at the expense of losing torque. That’s definitely not 100% accurate, but there is a kernel of truth to be found. Installing a lightweight flywheel — often made from aluminum versus steel — will decrease an engine’s inertia. While it technically doesn’t reduce an engine’s torque, driving the vehicle could feel that way. That’s because more torque will be required to get a vehicle moving.

This difference is particularly noticeable when launching from the starting line at a drag strip. On the street, drivers will need to be more careful releasing the clutch pedal from a standstill and possibly add more clutch slip than usual. A slight misstep with the clutch which might not matter with a regular flywheel could stall a vehicle with a lightweight unit.

On the flip side, the lightweight flywheel lets an engine rev more freely, so it’ll have improved throttle response and quicker shifts. That same sprightliness allows a lightweight flywheel-equipped engine to shed rpm more quickly too, which can enhance engine braking.

The proof is on the dyno

Approximately one decade ago, Hot Rod Magazine compared a regular steel flywheel versus a lightweight aluminum one using the dyno at California’s Westech Performance. Of course, Westech later became famous as the setting for “Engine Masters,” a part of the Roadkill television show empire. The weight of the regular steel flywheel was 31 pounds, while the lightweight unit clocked in at a mere 15 pounds.

On a modified 383 cubic inch small-block Chevy, the lightweight aluminum flywheel made 7 horsepower more than its steel counterpart, not to mentioned an extra 9 lb-ft of torque. Although ironically, that engine could feel less torquey during normal street driving, especially when starting from a dead stop.

So should you run out and buy a lightweight flywheel and start looking for an excuse to split the engine and trans to install it? Without question, it will increase horsepower via lower rotating mass, and your engine will feel more snappy — once it gets going, that is. It’s a worthwhile modification for road racing types and canyon carvers. However, if your car is mostly street driven in stop and go traffic or you’re an avid drag racer with your dreams set on buying your own drag strip, you’ll probably want to retain a stock-style steel flywheel.