So to the heart of the matter. To ‘9A3B6’, as it’s known internally. Porsche describes this 3.6-litre turbocharged flat six as “completely redeveloped”, suggesting that rather than being entirely new, it is derived from the 3.0-litre twin-turbo unit that has served in the 911 since the Carrera went to forced induction in 2015.

The extra capacity is the result of the bore increasing from 91.0mm to 97.0mm and stroke rising from 76.4mm to 81.0mm. This engine has new internals and mounts, a more compact intake manifold and cylinder heads, and it uses more direct-acting finger followers for the valvetrain – the old engine’s VarioCam Plus variable valve lift is no longer required. The crankshaft counterweights are also lighter.

It generates 479bhp of the GTS’s hybrid-enhanced total output of 534bhp (the previous GTS made 473bhp). The 400V electrical circuit also means the unit can do without a belt drive and starter motor, and so despite being larger than the 3.0-litre twin-turbo on which it is loosely based, the 3.6-litre stands 110mm shorter.

The T-Hybrid element takes a form similar to what we have seen in so-called mild-hybrid applications (Formula 1 too). A Varta-made, rapid-cycling lithium ion battery supplies power to (and takes recuperative energy from) a motor inside the eight-speed PDK and another within the turbo housing, leveraging know-how from the 919. There’s more detail in ‘Technical focus’ (below), but note that the T-Hybrid set-up doesn’t give the Carrera GTS pure-EV driving ability.

What’s interesting is that peak boost has risen from 1.2 bar in the old twin-turbo motor to 1.8 bar here. So why does power from the ICE take only a tiny hike? Answer: to comply with ‘Lamda 1’ regulations in Germany. To minimise exhaust emissions, a perfect fuel-air mix is required at all points in the engine’s scope (rather than running rich on full throttle at the top end, for that bit of extra ‘go’). The new engine achieves this; the old one didn’t.

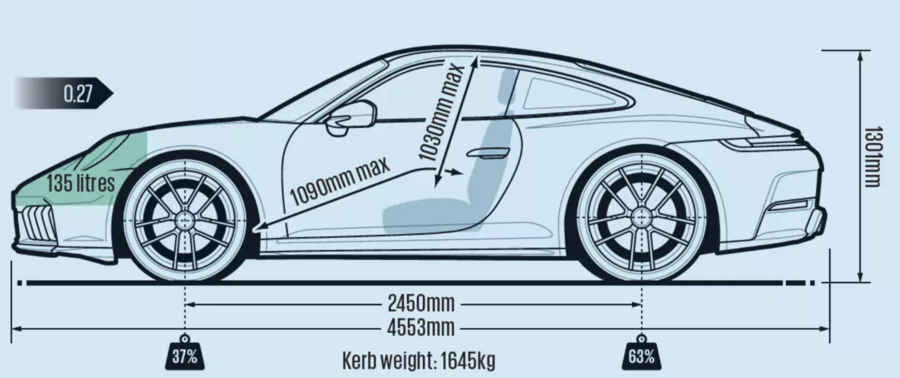

The T-Hybrid bits are said to add 50kg to the package. Our test car, which has optional lightweight seats and glass, trod the scales at 1607kg with its 63-litre tank full. This beats the claimed weight of 1645kg but is nearly 100kg more than the pre-facelift Carrera S we tested in 2019 (fitted with rear steer, front-axle lift and rear seats, so no weight-weeny). At the same time, the GTS undercuts the Ferrari 296 GTB PHEV supercar we tested in 2022 by 31kg and the current, non-hybrid Aston Martin Vantage by more still. Even in hybrid form, the 911 remains at the lighter end of the spectrum.

Elsewhere, the contact patch has grown over the previous Carrera GTS, if only at the back, and the 911 that in theory takes you halfway to GT3-level vigour still has helper springs on the rear struts of its 10mm-shorter-than-standard suspension, though the adaptive Bilstein dampers are faster-acting than before. Rear steer is standard this time too. The GTS can also have active anti-roll bars (PDCC), now powered directly by the hybrid system and even faster-actuating, though our test car went without.

Technical Focus

The new T-Hybrid arrangement in the GTS increases overall power and torque through electrification, but even more significantly it lays the ground for the 911 to meet future emissions standards.

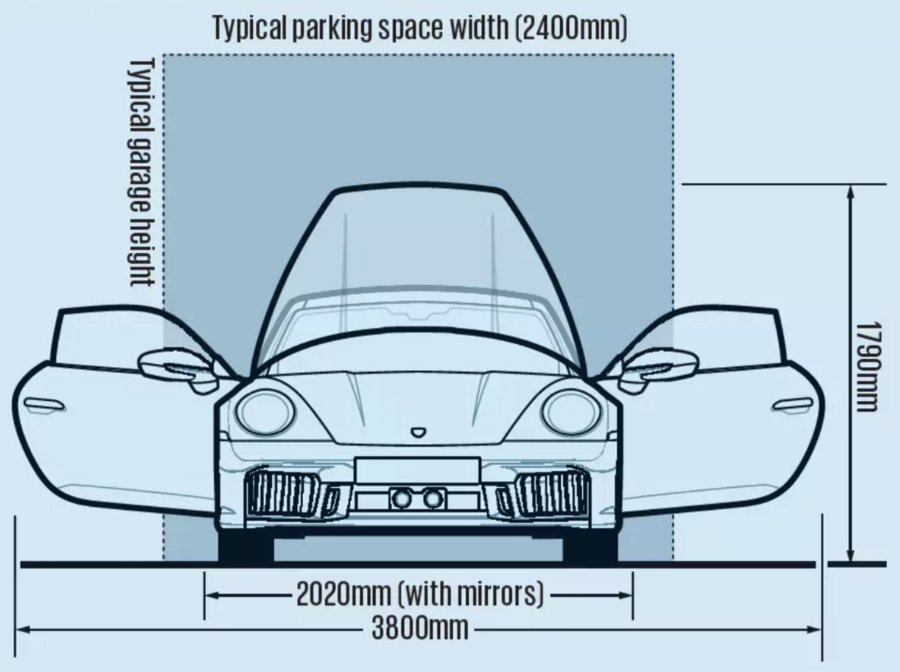

Here we have a circa-27kg, 400V battery nestled behind the front luggage compartment, powering an electric motor within the car’s large, solitary, 125,000rpm turbocharger (a unit that lurks between the exhaust and compressor turbines) and another motor inside the reinforced PDK gearbox.

All-electric running was never the aim, which is why the GTS doesn’t have a charge port and why the battery has a capacity of just 1.9kWh. By comparison, the Ferrari 296 GTB carries a heftier 7.5kWh unit beneath its narrow parcel shelf. Porsche says that, all in, its electrification of the 911 concept adds only about 50kg.

The e-turbo element of the T-Hybrid system is particularly interesting. The compressor can spool up extraordinarily quickly when given a push by the motor, which can output up to 26bhp. Result: throttle response comparable to that of a naturally aspirated engine, in theory.

There’s also no need for a wastegate as the turbo e-motor can decelerate the turbine should pressure in the system spike, with the energy generated (up to 11kW can be extracted from the exhaust gases) fed back to the battery or sent directly to the other motor. It’s a clever set-up. ‘Nimble’ might be a better description, because this lithium ion unit can simultaneously discharge power to the drive motor in the gearbox while recuperating electricity from the e-turbo. There’s very little wastage in energy terms.

The 400V system also means there’s no old-fashioned starter motor, so when you push the button, the engine fires that instant. With no need for a fan drive for the alternator and AC compressor, the crankcase is also 20% flatter, which creates space for the pulse-controlled inverter feed and the DC/DC converter.