Petrolicious, the creator of quality, original films and articles for classic car enthusiasts, has released its latest video, featuring Marco Diez’s low drag Jaguar E-Type known as 49 FXN.

After a couple of years away, the Petrolicious website and YouTube Channel has been recently rebooted by duPont REGISTRY Group, and new films are now dropping every Friday. Petrolicious celebrates the inventions, the personalities, and the aesthetics that ignite a collective lust for great automotive machines, and it seeks to inform, entertain, and inspire its community of aficionados and pique the interest of those who have been missing out.

Today, Petrolicious takes up Marco’s story…

The level of disconnect you can feel from the world is directly proportional to the amount of perseverance it took to build the tool. In this case, the tool is a Jaguar, shaped by hand, drawn from obsession, and assembled over more than a decade.

At first glance, it looks like one of the most elusive machines Jaguar ever built. Specifically, the low drag E-Type known as 49 FXN, an experimental, one-off outlier from the early 1960s that traded grace for grit and ended up more beautiful because of it. This car channels that same energy. It’s technically a replica, sure, but calling it that feels like using a spreadsheet to describe a hand-hewn sculpture. The word feels too reductive.

The original Low Drag Coupes were Jaguar’s short-lived answer to Ferrari and Aston Martin in international sports car racing. Born from the E-Type platform, the cars were reimagined for aero efficiency, trading the roadster’s romance for long tail practicality. Only three were built by the factory.

But 49 FXN was different. It was developed by British privateers Peter Lumsden and Peter Sargent, who collaborated with a young aerodynamicist named Dr. Samir Klat, then a mechanical engineering student at Imperial College London. Their goal was to compete at Le Mans and build something capable of taking the fight to Ferrari on sheer aerodynamic merit. What they ended up with had more presence and menace than anything else Jaguar put on the grid.

It raced. It lost. But it left an imprint, visually and viscerally, that never faded. That’s the silhouette Marco Diez fell for. “I also think that prior to the safety regulations, basically you could put on the road whatever you wanted,” Marco said. “If you could dream up a shape of a car with very few roadblocks, you could just put it on the road.”

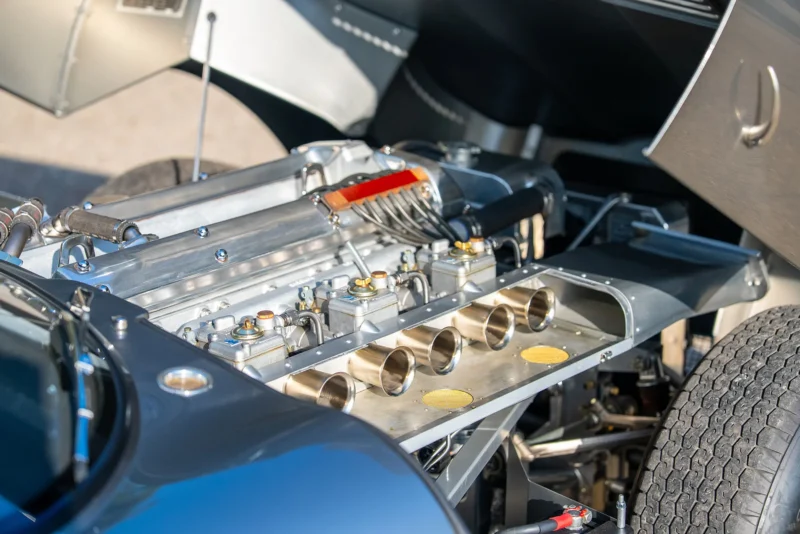

He didn’t just buy a body shell and bolt things together. He chased an idea into the weeds. Every panel was formed from flat aluminum by RS Panels in the UK. The engine is a 3.8 liter lightweight spec inline six, fed by a set of Weber DCOE side draft carburetors, a nod to performance tuning rather than period correctness. Jaguar originally used SU carbs, or in some race applications, triple Webers mounted upright. The DCOE’s bring both aesthetic drama and sharper throttle response. Under the clamshell bonnet, with hard fuel lines bent by hand to thread cleanly into the carbs, they look as much like sculpture as they do hardware.

Inside, the cockpit follows the same philosophy. The switchgear is sourced from RAF fighter planes, not just for the visual impact, but for what it says about the car. Purpose. Precision. Reliability. These weren’t toggle switches from a catalog. They were designed to survive combat. They click with intent. They do one thing, and they do it without fail. It’s exactly the kind of tactile, overbuilt, no nonsense interface Marco was chasing. “It was just the combination of the sleekness that the E-Type is known for, but the muscularity that it’s not known for,” Marco said. “That’s what sold me on this car.”

The steering wheel? An Aston Martin rim, repurposed and topped with a Jaguar C Type horn button. Every surface inside the car, every gauge, bolt, and fastener, was handpicked, modified, or made from scratch. “Every surface was thought about,” Marco said. “That bolt was thought about. What thread it is, what head style it is.” It’s beautiful, but every line has a job to do. Form is function, especially when the function is to disappear down the circuit.

At one point, Marco nearly walked away. “It took a really long time for a variety of different reasons,” he said. “At one point, I actually thought about getting out of the project.” The project had gone too deep, demanded too much. But that same depth became the thing that connects him to the car today. “All I hear is the engine. All I hear is the downshifts. It’s like this Zen thing for me, as I am sure it is for many people.” Because when he drives it, there’s nothing else.

And that’s the real story. This isn’t just about Jaguar, or Goodwood, or even 49 FXN. The story is what happens when you pour yourself so completely into something that the only way to hear yourself again is to go for a drive, the same kind of drive that can only happen when the tool you built cost you everything but gave it all back in return.