Mitsubishi joined Audi and Land Rover on Friday in holding new cars at ports in response to new car tariffs. A new report says unprocessed cars are beginning to fill up storage lots at U.S. ports, and transportation workers say the backlog of cars could snarl shipping logistics if nothing changes.

They Don’t Pay a Tariff (Yet) on a Car Held in Port

Why would an automaker refuse to pick up its own products from ports? Because they don’t pay a tariff until they process the car out of the port facility.

The Financial Times explains, “Fees for holding cars in port are high, and carmakers are also seeking to move vehicles into U.S. bonded warehouses, where manufacturers can temporarily store products without being charged tariffs.”

Most Automakers Have Enough Inventory for Now

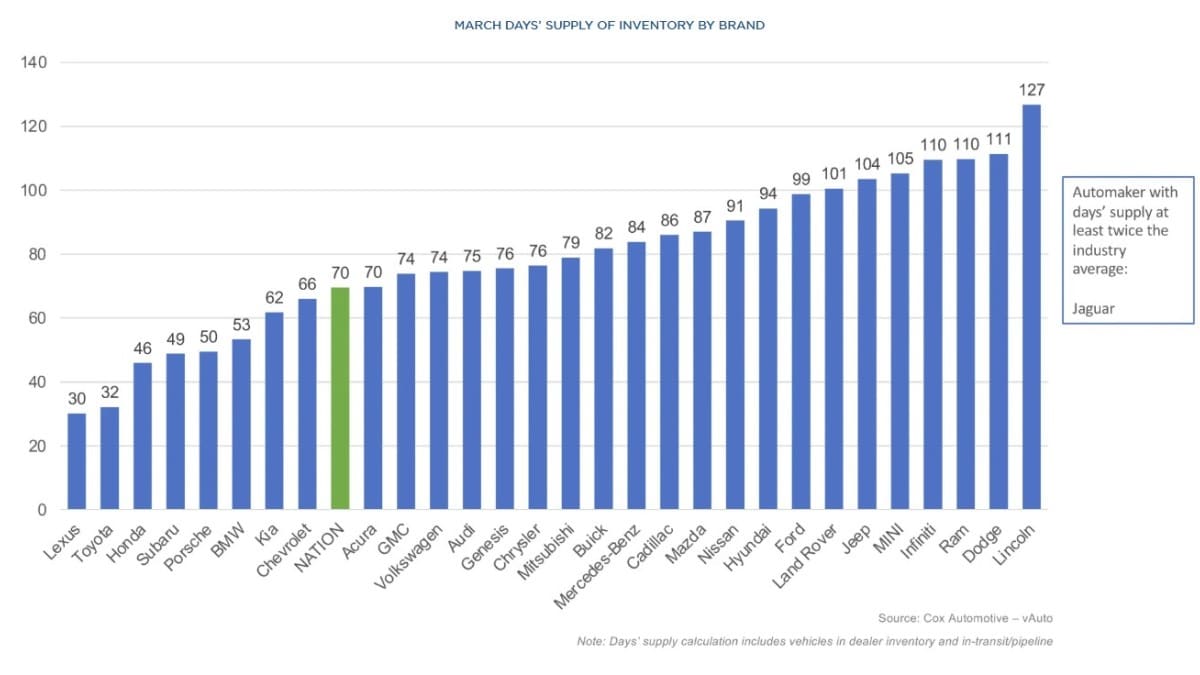

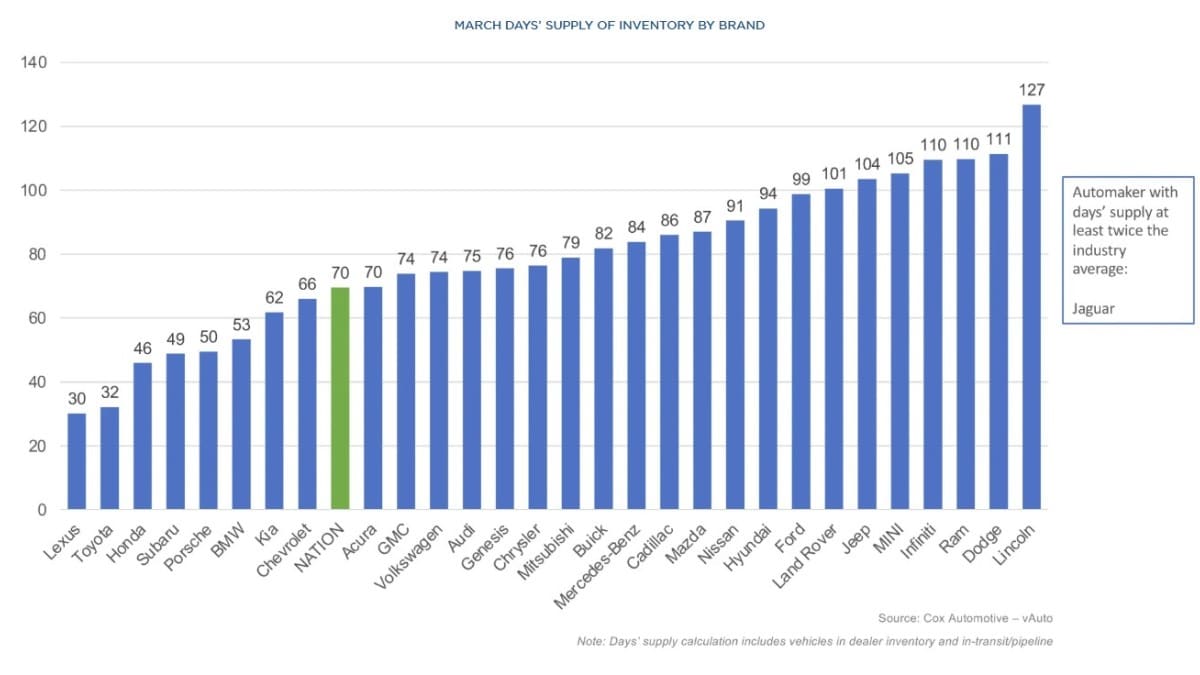

Balancing supply and demand is key to automaker success. Most carmakers traditionally try to keep about two months’ worth of cars on sales lots at any given time, with another two weeks in transit. More can be a waste of money (particularly for dealers, who are usually making payments on the cars on their lots). Fewer might mean missing out on sales because they lack the combination of colors and features a buyer wants.

The average automaker entered this month with a 70-day supply — not far from the target. That’s shrinking as sales speed up. Many Americans have flocked to dealers in recent weeks, looking to buy the last cars imported at pre-tariff prices.

However, Land Rover and Mitsubishi are comfortably above that target. Audi is nearly at it.

Mitsubishi spokesperson Jeremy Barnes told industry publication Automotive News, “We have sufficient stock on the ground at dealers for the moment to not impact customer choice.”

Move Could Pay off if Tariffs Are Lifted

If the tariffs last longer than inventory, automakers will have to pay higher post-tariff prices to import the cars. But President Trump has already wavered on some tariffs, enacting a 90-day pause on non-car duties.

Companies may well be gambling that Trump will waive the car tariffs before they run out of inventory.

Port authorities, however, are likely to start objecting soon. “We are getting closer to capacity at some ports,” one anonymous logistics executive told the Financial Times. Another “warned that the piling of imported vehicles at American ports could get ‘quite ugly’ with ports set to ‘fill up fast’ in a few weeks,” the FT reports.

Port workers are already bracing for chaos as planned port fees in the millions of dollars per ship could soon concentrate shipments into just a handful of already-busy ports, causing supply chain bottlenecks that could rival those of the early COVID-19 pandemic.