The heyday for the National Hot Rod Association’s (NHRA) Top Gas dragster class was 1961 to 1971. Unlike their nitro-huffing counterparts in Top Fuel, Top Gas cars used regular old pump gas. Nitromethane makes crazy power thanks to its more thorough combustion (more on that later), so running gas was a severe handicap. To be competitive in the Top Gas class, you had to get creative. Lots of builders settled on two engines as the solution, but how do you get them to play nice with a single axle? You could do like Car and Driver did with its two-engined Honda CRX and just put a separate power train in the back, but that’s not how Top Gas attacked the problem.

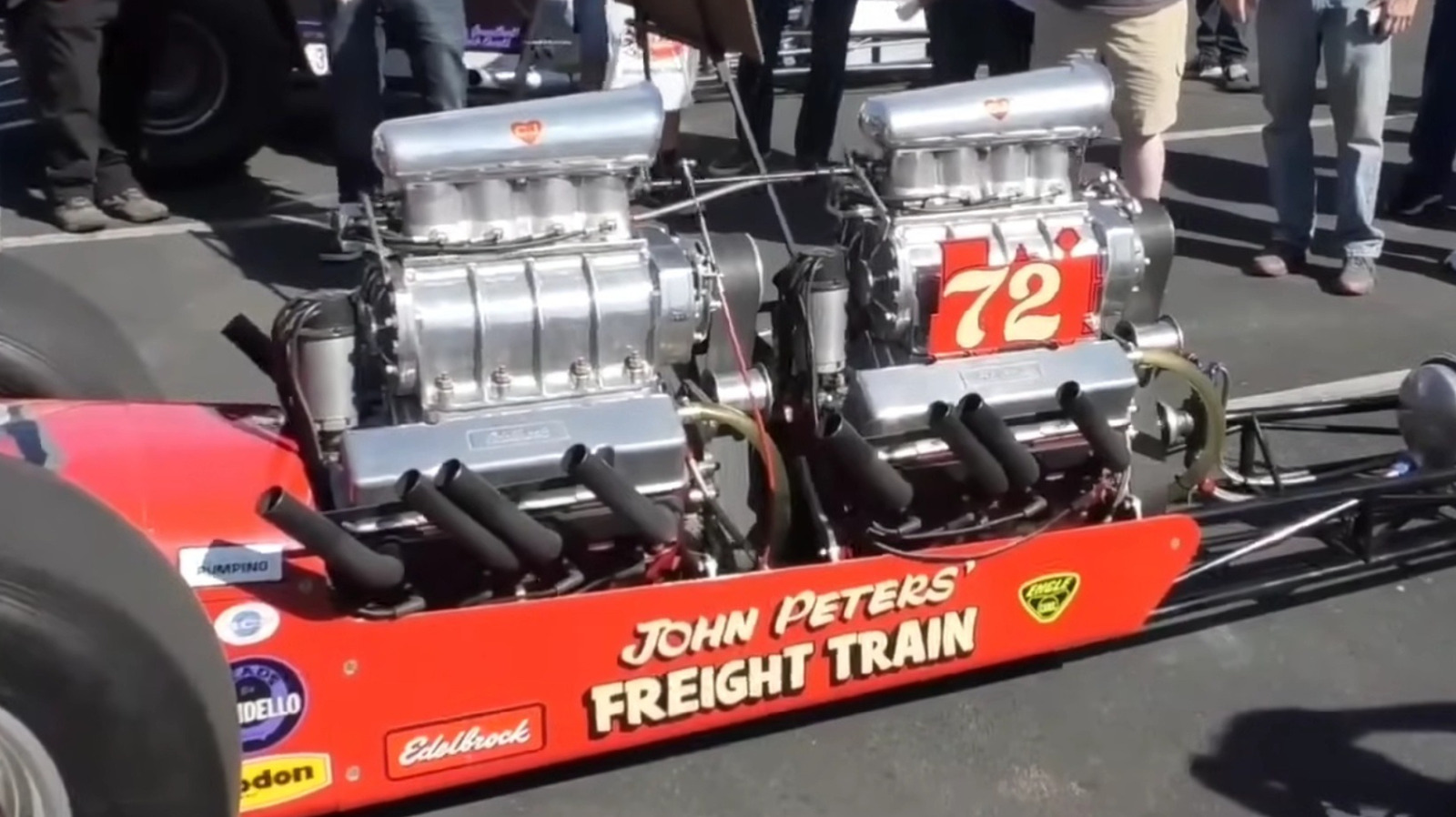

The all-conquering Freight Train dragster was running about 1,600 horsepower in 1971, Top Gas’s final year. Or rather, it was making 800 plus 800, because that figure came from two bored and stroked 428-cubic-inch first-gen Chrysler Hemi V8s literally chained together to make a V16 with a space in the middle. The two engines ran as one because builder John Peters transformed supercharger drive hubs into sprockets and used double-roll number 50 chain to connect them, then routed the rear engine through a two-speed transmission as you would with any normal power-train setup.

Eddie Hill’s Double Dragon used a pair of supercharged Pontiac V8s in an opposed, side-by-side setup, running like twin linebackers shouldering their way down tracks together. Rather than connect the engines directly and force them into lockstep, he gave each its own flywheel, clutch, driveshaft, and individual ring and pinion gears on the rear axle. It worked well enough for Double Dragon to hit 202.7 mph in the quarter in Hobbs, New Mexico and rip chunks off the pavement from the track in Indianapolis.

Multiple engines are a drag, an awe-inspiring drag

The twin-engined Top Gas dragsters left a lasting impression on plenty of people, and there are modern re-creations with their own ingenious ways of linking two engines to a single gearbox. One of the more impressive, insane examples is Rocky Phillips’ Evil Twin (above). He combined two small-block Chevy V8s by letting the flywheels act like a pair of giant cogs. Of course, this means one of the engines has to spin in the opposite direction. He managed to get the right valve timing in the backward-running engine thanks to a camshaft from a Chris Craft boat V8, which ran in reverse by design. Phillips could then attach a clutch or torque converter to one of the flywheels to run through a transmission back to an offset differential.

While multi-engine setups are nostalgic for drag racers, they’re pedestrian at tractor pulls. As a kid, I saw tractors featuring the most diverse, unfathomably cool power trains that would have been a bit over the top in “Mad Max.” You won’t hear anything more terrifying — and life-affirming — than a tractor with three Allison Aircraft V12s dragging a sled over 320 feet.

(Warning: if you take your kids to a tractor pull, they may force you to help them make a remote controlled mini tractor pull rig. Side effects include a sense of accomplishment and happiness.)

While tractor builds vary, one typical setup gives each engine its own clutch and driveshaft that route to a single gearbox, which can be crafted to recieve power from whetever number of engines you prefer. From that gearbox, the combined power of all the engines will flow to a transmission or a single-speed unit that just provides forward, neutral, and reverse.

Nitro is the answer, a scary, explosive answer

Nitromethane burns with terrifying explosiveness and can even manage combustion without needing air. Gasoline, though energetic at 31,000 calories per gallon, equivalent to 110 McDonald’s hamburgers, can’t compete. It takes about 15 pounds of air to burn a pound of gasoline, but just 1.7 pounds of air to burn a pound of nitromethane, when it does use air. You don’t need much nitro for complete combustion.

When dragsters first started using nitro, speeds were getting so quick that the NHRA feared it might lose insurance, so it banned nitromethane in 1957. When nitro returned in 1963, Top Gas had been running for two years. The attitude of Top Gas competitors toward Top Fuel may best be summed up by John Peters, builder of the Freight Train tandem-engined Top Gas car, in an interview with Greg Sharp in 2011, republished on Wagtimes: “Running gasoline is a challenge. It takes more than adding 10 percent and some overdrive. Nitro isn’t even a fuel. It’s an excuse.”

In 1978, Top Gas reappeared. It still required pump gas as the only fuel, but eliminated supercharging and stipulated that the cars use torque converters. What didn’t reappear were twin-engined dragsters, and not because they were banned. They just weren’t necessary. The supercharged dual-engine Freight Train’s quickest time by 1971 was 6.95 seconds, while Lena Williams ran a single-engined Top Gas car with no blower to a 6.98 in 1983. Multi-engine setups work in a tractor pull because speed isn’t the goal so much as raw pulling power. In dragsters, weight and aerodymanics are larger inhibiting factors, and once single-engine power is high enough, adding a second plant isn’t necessary. Case in point, Brittany Force does just fine, hitting 341.85 mph with one engine.